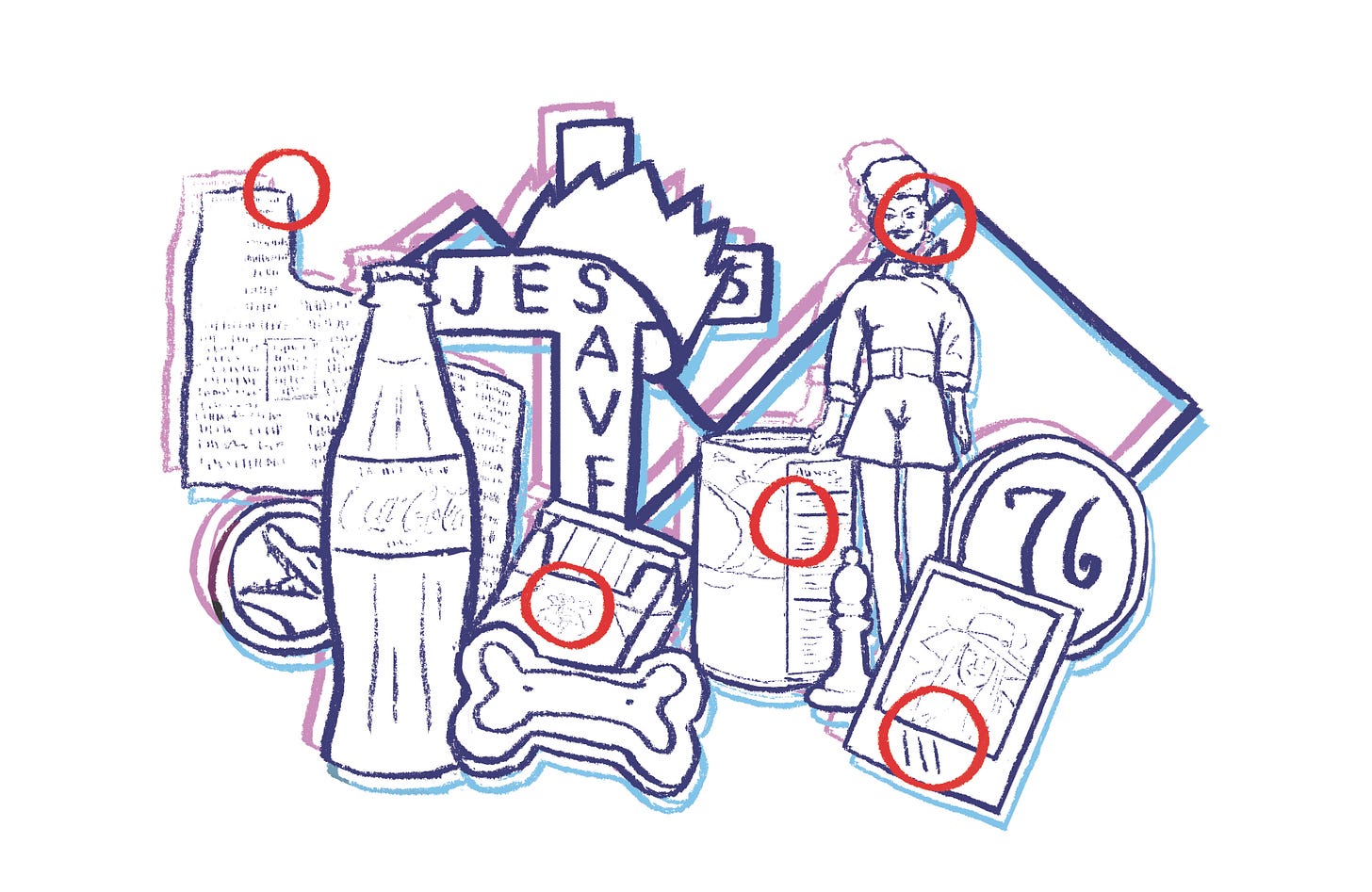

There's Nothing to Solve, You Know?: Origin Stories, Easter Eggs, and Under the Silver Lake

"It's silly wasting your energy on something that doesn't matter."

“…For now, the answers remain hidden, deep below the surface, under the silver lake…”

Sam’s rent is criminally overdue, and he’s wondering what his neighbor’s parrot is saying. “‘Not a friend?’” guesses his unnamed casual sex partner, an actress (Riki Lindhome), who stopped by with lunch and the promise of a quick fuck on the way to a…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Brianna's Digest to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.