Here’s what happened the day my apartment burned down: I was at my parents’ house, three hours from Brooklyn in Sturbridge, Massachusetts, when I received a text message from my friend: “Christa’s Kitchen is on fire.” The grocery store directly adjacent to my building. I acknowledged the text with concern, but not yet panic. I sent him a series of questions in response. How bad is it? Is it spreading to our building? Does our building look ok? Does the fire show signs of slowing down or stopping yet? None of these inquiries yielded the answers that I wanted, but I didn’t necessarily receive answers that I didn’t want, either. Every reply was mostly just a lot of “I don’t know. It’s hard to tell. It looks like it might be contained. I’ll keep an eye on it for you.” My parents always taught me to quell my instincts of jumping to the worst possible conclusions; panicking about events that may not even come to pass. I’ve never been good at doing it myself, so they did their best for me. I paced around, my nerves tightening into coils in every room of their house. My mom assured me that things would likely be alright. That there was the possibility of some damage, but nothing to get hysterical about yet. Why work myself into a tizzy when I don’t even know the full picture?

For the rest of that evening on May 1st, I remained unaware that that small rooftop fire on Christa’s Kitchen had bloomed into what I eventually learned was regarded by many as even greater than a five-alarm blaze. It consumed not only my apartment building but the one next to it on Cooper Street, and the two buildings touching the opposite side of Christa’s Kitchen on Bushwick Avenue. I continued to communicate with a small handful of friends who spurred more questions than answers for me. I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t distract myself with a movie, or a book, or whichever Real Housewives series I was working my way through at the time. Buddy, my family’s parrot, would perch on my shoulder and fuss with my hair and I’d completely forget she was even with me. When I feel fear, I become catatonic. I slept, but not well. I would not learn that I had lost almost everything until 48 hours later.

No one who owned my building was allowed to go inside until it was cleared for entry by the city. But over the following two days, after the blaze which consumed Christa’s Kitchen had finally been vanquished, it became clearer and clearer to me that I did actually need to worry and panic about the state of my own building. There was a growing likelihood that, despite the fact that our building was still standing, despite the fact that the front-facing facade appeared mostly unblemished, that it still had incurred substantial damage elsewhere. Somewhere unseen. Perhaps, a place not visible to my neighborhood friends on the street giving me updates from afar, or the cable news videographers circling above who had nonetheless caught a millisecond of footage which showed ominous smoke billowing perilously close to my bedroom at the back of the building. But since my roommate had, after the flames were extinguished, sent a fireman into her bedroom to retrieve her medications (she was luckily not at home during this whole event, either) and was told that things “looked ok,” I thought maybe there was a chance that everything had actually worked out. That if her room was “ok,” then mine was as well.

This was not the case. I now know that if something looks “ok” to a firefighter, you can just assume you’re being fed a load of bullshit. I was also fed bullshit by our neanderthal super, who had told me over the phone as the fire lay waste to the building he worked in, that “Nah, everything’s gonna be fine,” and I wish I could track down that stupid fucker and strangle him. My room was destroyed. Many people have seen the photos, because I’m overly liberal about posting them. The fire was, as I’d feared, at its worst behind the building, from the backyard where I’d wake up in the mornings and spy on the doves, blue jays, and catbirds making little symphonies from my window, and the two squirrels, one grey and one black, playmates who would chase each other around my fire escape. I used to brew drip coffee for Brian and lay in bed with him and look out the window, use an app on my phone to count and identify every unique, chirping call. But now the trees were ash, and my room was a wet, sopping mass of soot, exposed wood, flattened furniture, and mangled treasures.

The evening before I learned the reality of what had happened, I went out for ice cream with my parents. I can still feel how that knot of worry in my stomach stole any small pleasure boost brought on by the sugar rush. On Friday morning, my roommate was the first person allowed inside 63 Cooper Street, and I woke up to her telling me that my room was gone. That is literally what happened. My alarm went off, I sprung forth from my parents’ futon following the worst sleep of my life, my phone rang, and seconds after my “Hello,” I heard, “It’s gone.” I would never listen to the birds chattering to one another or watch those two squirrels play together from that bedroom again.

Maybe others would have crumbled in this situation. It’s something that Brian likes to tell me a lot: That my wherewithal in dealing with this was nothing short of awe-inspiring, that many people might have used such a traumatic event to give up on New York, move back in with their parents, and he wouldn’t have blamed me if I’d have been one of them. But I’m a proactive person, I’m pragmatic. These are qualities that I was already aware I possessed, but now I acknowledge their sheer necessity. I’m not inclined to stay put, to let feelings of despair overwhelm and paralyze me permanently. If my breakup the previous year had taught me anything, it’s that I’m good at identifying my pain and taking steps to ease myself out of it. I carve out a path, and then I clear the brush that’s scattered overtop.

I guess this is the crucial thing about me: I don’t like feeling bad when I know I have the power to make myself feel better. In this way, I quietly resented being told by people, even my boyfriend, how brave I was. It didn’t feel like bravery to me, it just felt like the only thing I knew how to do. So, why wouldn’t I do it? How is it bravery to be forced into horrific circumstances and simply refuse to give in to them? It didn’t, and still doesn’t, feel like anything to be proud of. It just felt like the only logical course of action. I don’t think continuing to live my life not succumbing to grief is a particularly commendable feat.

I learned that I had lost most of my belongings that Friday, and I went back to Bushwick two days later—to the scene of the crime. I crashed at a friend’s apartment a few blocks away from my ashen abode while I gathered my bearings, salvaged belongings, and hunted for a new place to live with my same roommate. My dad drove me into Brooklyn and spent that first night with me at my friend’s place, which would become my temporary home for the entire month of May. The next morning, he helped me and my roommate with the first rescue mission, when we entered the black building together, the damp turning to mold and hollowed out with the residue of disaster. It smelled like the worst barbecue ever, sharp, smoky and a little sickly sweet, a pungent perfume which still clings to my coats even after a trip to the dry cleaners now a full year past. I managed to collect some mostly unharmed items, like my DVDs and Blu-rays, the coats, and some other assorted goods, which could be ferried in my parents’ car and cleaned back at their house.

Even now, I don’t really like to think about the two days I spent scrabbling over the desecrated remains of my bedroom. Yet I haven’t deleted the photos I took on my phone for insurance purposes, and I’m not really sure why. It’s like I’m committed to holding onto proof that it happened, or proof that I used to live there. Or proof that underneath all that wreckage, there were remnants of a life.

Dealing with the Fact that Your Apartment Burned Down and You Just Lost Most of Your Stuff, a Guide:

You call your renter’s insurance as soon as it happens and you get started on a claim. You tell them things like where the fire happened, when the fire happened, who started the fire, and how much money everything that you lost probably amounted to. You think really, really hard and you make an unquantifiable list of everything you probably owned and lost, and you make wild estimates as to how much all of it may have cost you throughout the entire course of your life, and then you get overwhelmed and you freak out at your mom because doing this feels impossible, because how am I supposed to know how much money I spent on all my possessions throughout the entire course of my life. But you do your best, and then the claims adjuster steps into your burnt apartment two weeks later and says, “Jesus,” and after a month you receive your policy maximum anyway—an amount which covers most replacements, but not all.

And when things like this happen, people say that at least nobody died—and nobody did. Material items can be replaced, but lives cannot. I know this. But it’s not even the fact that there were obviously many things I lost that cannot be replaced, like heirloom jewelry my mom gave me, or handwritten notes from my friends when we were kids, or my movie stub collection which included Cats & Dogs, a movie I don’t even remember seeing but the ticket proved that I was there; or my grandmother’s sunglasses, the ones I had wanted to someday fill with my prescription so I could wear them myself.

It’s the fact that even the replaceable items carried bits of me in them. The contents of that room once filled up my childhood bedroom, then my first apartment after we sold that home, then my parents’ new home in Massachusetts, and then my first apartment when I moved to New York. I was in those tacky posters, in those clothes, I was in the knick knacks and the old greeting cards, the costume jewelry and the Halloween decorations. These things are all replaceable, but that room was my garden. It weathered storms and sunshine, high school boys and breakups, new friends and bad ones, it moved from state to state. It was mostly expendable, but it was still me, and it was gone.

When I followed the news coverage of the LA wildfires earlier this year, I felt guilty. A weird reaction, I know, my therapist told me. Hundreds, maybe thousands of people were now losing their homes to fires, to the same freak once-in-a-lifetime accident I’d already dealt with the previous year—and still hadn’t moved past yet. How could I still not be over it? Seeing the GoFundMe posts made me cry. It brought all the feelings back at once, and carried some new ones with them. I know what these people have been through, what it feels like to suddenly be faced with the reality of displacement; that all the little things you’d gathered up in your life, that made you you, were now disintegrated, smoke-damaged, or completely irrecoverable, physical collages of decades reduced back to a blank page one. It was a horrifying truth, and I felt shame for still feeling sad about my own. I don’t really show it, but I am. I’m sad all the time about it, even still. I make jokes and I laugh, because if I think about my room tangled in a mess of wood and wires, like a body with its guts yanked to the outside, I will cry and cry and cry.

And this made me feel so stupid, even if feeling stupid about it sounds stupid—and I know it’s stupid. But in that moment, it suddenly seemed silly to be mourning a single, silly fire from months ago, when countless others were now consumed with a greater horror all at once. A mass tragedy is occurring and you’re still sad about your own tiny little fire in New York City? How selfish! This is what my evil brain was trying to tell me, that I needed to compete in the Trauma Olympics. Which person who experienced a fire that destroyed their home deserves to be sad about it the most? But the truth is that all of these people affected by the LA fires will be grieving their life from before the fire for a long time, too. They’ll probably cry about it a year after it happened, and maybe again another year after that, and maybe again long past the point where they thought they’d already be over it. Maybe I’ll already be over my fire years after they’re still grieving theirs. Collective loss, but grief is still personal.

But experiencing a life-altering set-back will make you feel a lot of weird feelings; feelings that are ugly and unkind, and don’t really make sense. Sometimes I feel anger and resentment towards people who come to me with well-meaning sympathy for how burdensome my last year has been: My apartment burned down, my childhood pet died, I lost my job. (Kind, innocent) People will slide into my DMs to let me know that I’ve “had a rough go of things” and that I “don’t deserve all the shit that’s been thrown at me” and that I “really deserve a win.” Right, well… I already know that. I don’t mean to sounds ungrateful and glib towards the tender words from acquaintances, strangers, and friends alike. But it does make me feel like a charity case, like everyone can look at me with relief and think “at least that hasn’t happened to me.”

Maybe it’s partly my fault: Sometimes it’s hard to not treat myself like a charity case, too. But at the same time, it would be disingenuous to start posting inspirational Instagram carousels about how “strong” and “courageous” I am. I don’t feel very strong or courageous, I just feel tired.

There are things in life you don’t really think about until your apartment burns down. For example: some stuff that is replaceable is not replaceable—at least, not immediately. If you live on the East Coast like I do, you can’t get an entire four-season wardrobe in the summertime. And you can’t rebuild a record or book collection if you don’t even remember what records or books you lost, because you weren’t a psycho who catalogues all your physical media. It’s why I’m so relieved that, incredibly, all my movies were perfectly intact on their shelves, aside from some debris and water damage on the cardboard sleeves and paper inserts, muddying the aesthetic purity of my Criterion Collection discs but not the quality of the discs themselves. When my dad slid my old copy of Talladega Nights into my new Blu-ray player to only watch the scene that introduces Sacha Baron Cohen’s character, it still played as good as new. I had established that movie collection across the span of 15 years, starting when I strode into the big thrift store on Main Street in Lansdale, Pennsylvania one bare-skinned summer day and searched for a used copy of American Psycho that I somehow managed to find, that I needed to find because I’d become obsessed with the film via Tumblr without ever having actually seen it yet.

If your apartment hasn’t burned down, you don’t really think about the fact that your things that are replaceable are still a pain in the ass to reacquire. I’d kept a large, eclectic collection of beauty products—skin/haircare and makeup—most of which I didn’t use on a regular or even monthly basis, but sometimes it was just nice to have that one weird product I forgot I had for that one weird time I really needed it. Now, I don’t even remember half the products I once owned, and I probably never will. And you also don’t think about how other replacement items will never carry the same memories or meaning again. My records were mixed with hand-me-downs from my dad, my bookcase carried bits of ex-boyfriends; my wardrobe, the most brutal assemblage to lose, held college-age H&M turtlenecks still in mint condition, that I was proud to have hung onto as proof that fast fashion used to be better made.

I’m trying to be intentional about what I purchase. I hate fast fashion, and I want belongings that are made to last. But when your apartment burns down, you’re not really thinking about sustainability. You’re thinking about how you have nothing, and now you need to have something again. I hate all the clothes I own now, because most of them were bought in haste, in the frenzy just to have things to wear at all. And as ludicrous as it may seem, I’m constantly giving pieces over to second-hand shops so I can receive credit in return for things I might like more. Every time I go out searching for new outfits, I am thinking about what I still don’t have and about how I don’t like what I do. I no longer feel held by a bevy of pieces lovingly amassed across decades, trends, and phases of my life; just an aggregation of stuff forced upon me in response to a random, life-changing catastrophe.

I’m not assuaged by the idea that someday, all these alien items will be really and truly mine. That because I now own them, they are no different than the items I lost. That even if it doesn’t feel that way right now, this stuff has become part of something that will someday be meaningful to me in the same way the things I lost once did, because that’s just what happens over time, as you live your life, as you exchange currency for goods and services in the marketplace of a capitalist economy. But that time is not now, it is years down the line. I already had what was mine, I’d nurtured something that is now dead, and none of these futile substitutes carry any life in them. I have no backlog anymore, no history; no foundation of Brianna with space to expand. My home is full of foreign objects purchased out of need and not pleasure, and they are gripped with the same stink of pity and tragedy like what still clings to the few familiar items rescued from my ruined life.

Our building is old, and big, and it faces a busy main road, so my days spent at home are noisier than what I was used to. We’re adjacent to an extremely wealthy sub-neighborhood in South Brooklyn, a convergence of Caribbean immigrants, Hasidim, and various settled-down, young families. If you’ve never been here before, it’s genuinely surreal: Stately Victorians and mini mansions practically stacked on top of one another in the middle of Brooklyn, dense foliage, front lawns and driveways aplenty. Back in October, on one tipsy walk home from the train after a New York Film Festival party, I was led into one of these homes by a Hasidic family who requested a few moments of my time to be their Shabbos Goy for Rosh Hashanah (I am actually Ashkenazi Jewish on my dad’s side, but I’m sure that wouldn’t count to Hasidim anyway).

This was one of the funniest things I’ve had happen to me since moving here, but it’s mostly an uneventful area despite how aesthetically lovely it is. It’s an older and more family-oriented neighborhood than what I would have liked, if I’d really had a choice. For now, I’ve been indefinitely priced out of the young, trendy North Brooklyn, which would have happened one way or another through rent hikes. My new apartment is rent stabilized, and I do feel overwhelming relief that I can finally post up somewhere for a few years without too much annual financial worry hanging over my head.

Still, when I lived in Bushwick, it was just nice to be surrounded by a lot of people my own age. Bushwick gets a bad rap for basically having become a playground for, as what Elaine Benes once called Kramer, “hipster doofuses.” DIY bands, DJs, wolf cut hairdos, hip bars and clubs I’ve never been to and never will because I proudly can’t hang, and basically just people who talk about living in Bushwick. I think it has a worse reputation online than what it is in real life, but admittedly I was not a part of whatever was “going on there” that seemed to “matter.” I lived in what I used to affectionately call “the ass-end of Bushwick,” basically straddling the neighborhood of Ocean Hill. It was pretty quiet and away from the riff raff while still being accessible and lively, and still felt like city life as opposed to where I live now, which is basically the suburbs with some city sprinkled in.

I liked living in Bushwick, and it was always nice getting on the train, walking around and seeing a lot of people my own age, dressed like me, and now on those rare occasions I do find myself taking the L, it is comforting to be among my peers again even if many of them look like they’d instantly piss me off if we found ourselves in conversation. When I board my new local line in the summertime sporting short-shorts and tattoos, I sense I’m being disapproved of by parents and the elderly, and the Hasidic men who evade my person completely.

Everyone likes to tell me how much better my new apartment is. But I don’t really care, because I miss my old one. I loved my burned-down apartment, and I would’ve stayed there as long as I could’ve afforded it, even though there were no windows in the common areas and the pipe connected to the HVAC kept leaking into my bedroom. One of the last things the maintenance guys told me before the apartment burned down was that the entire pipe may have to be replaced, which would have upended a huge chunk of ceiling in my bedroom. I wasn’t really looking forward to that likelihood, and it is bittersweet to not have to worry about it anymore.

It’s been one year this month since the fire, and I live in a home mostly consisting of things I acquired less than a year ago. When I first moved in, I would cry over the fact that my surroundings felt unknown and hostile—but what can you do. It’s a little easier now that I live with Brian, and the space with which I can truly call “mine” extends further than just my bedroom. It also helps to still have a few friendly, familiar things scattered throughout the apartment, a mixture of belongings that I snatched from the wreckage and belongings that weren’t ever there. From the fire: Two stuffed animals (including my favorite and oldest, an Easter gift from when I was eight), my aforementioned movie collection, two albums full of photos I took myself when I was a kid; my Kitchenaid mixer, scratchless, fully intact with all its attachments, could probably survive a goddamn missile strike; my little ficus plant, miraculously, which had been fully shielded from the terror behind my bedroom door, subsisting for a few days off of hose water which had happily saturated its soil and only withering a little from a lack of light that was quickly remedied. It is now thriving in my new bedroom, and its leaves have reached larger sizes than that of my hands. Not from the fire: Some art created by my mom, and some photographs taken by my dad.

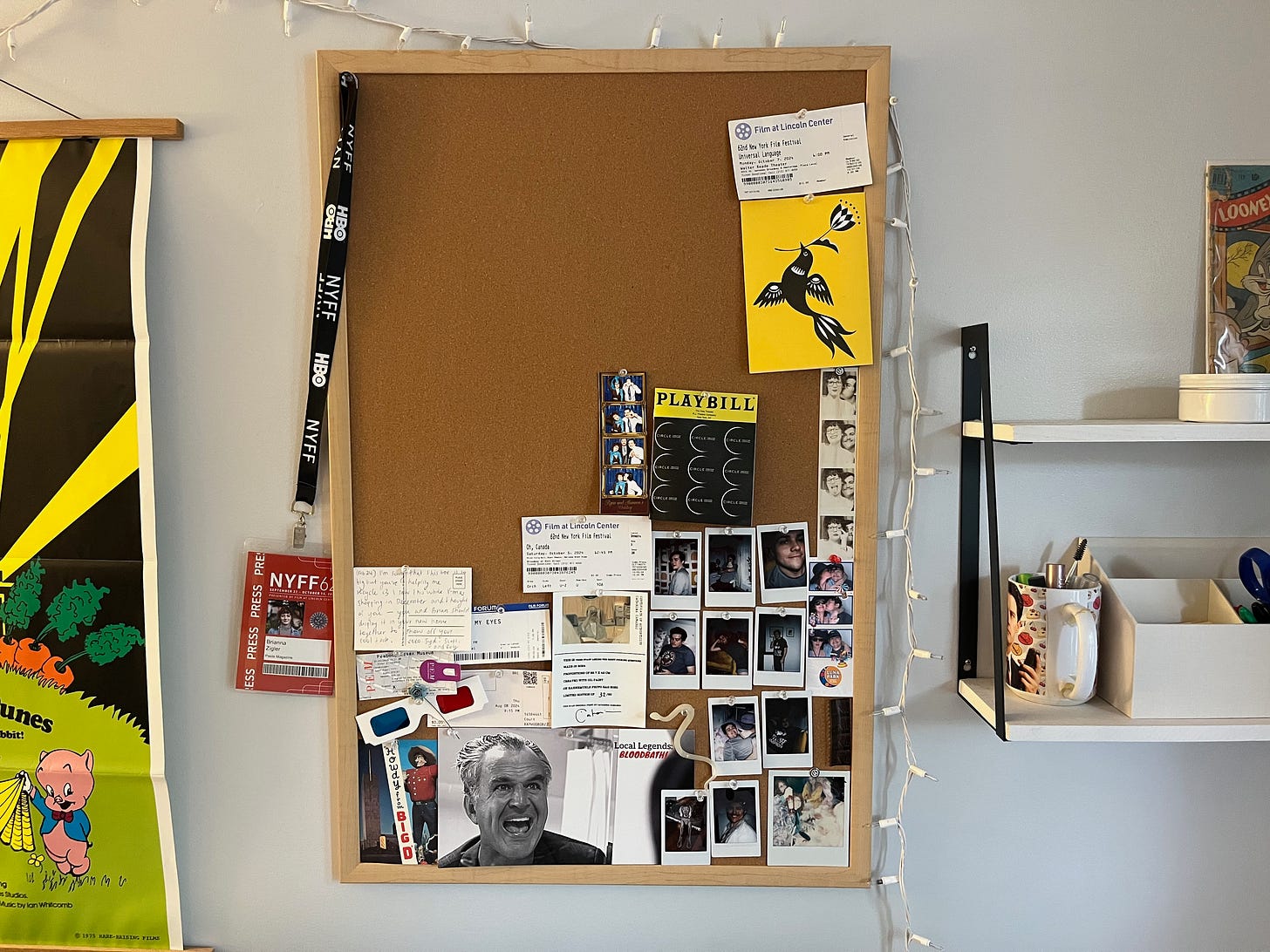

One of my most dire losses was a large bulletin board that I’d brought with me from room to room and state to state, a growing collection of small curios, notes, tickets, and mementos affixed to the cork which I began decorating when I was 13. I kept an autographed receipt from when I worked at Panera Bread in high school and The Wonder Years frontman Dan Campbell visited for lunch, candygrams from middle school friends I didn’t even like, a metal washer that my goth acquaintance had made in a high school trade class; a setlist for the band Transit from a pop punk show, and the professional photos taken at my freshman formal. Each time I moved, I would simply lay the board carefully on its back atop all the other bits and bobs in my car, so that the papers and small tokens would stay in place. It had remained perfectly preserved from Pennsylvania, to Massachusetts, to New York City. The “Bulletin Board of Memories,” as I so banally called it.

I have started up a new “Bulletin Board of Memories,” and so far, it is largely comprised of photos of Brian, which I have in itself dubbed “The Wall of Brian,” next to some scattered ticket stubs, postcards, and other Little Objects. It’s hard to cope with the fact that the physical keepsakes I saved from the first half of my life are all gone, because the keepsakes I save now feel less precious as I’ve begun their accumulation in adulthood instead of as a teenager. There is something almost magical about saving the bits of you from the most vital developmental years of your life. That Brianna doesn’t exist anymore, but she was preserved through the silly notes and the toy keychains and the train tickets for places she may never return to. I’m 30 now, and the me that I am is likely the me that I’m always going to be, and it was comforting to keep close the me that I will never be again. Even so, as the kids like to say: we move. What else can you do, really?

When I wake up in the mornings, I can sometimes hear my upstairs neighbor screaming at the people he sells drugs to, because it seems he’s not very good at telling these people that they need to leave his apartment eventually. This might make it sound like I live in a worse place than I really do—I live in a spacious, first-floor, two-bedroom unit, and the upstairs neighbor is not all that bad. I’m also used to him at this point. He is an extremely odd, probably unstable guy, but he doesn’t actually bother us, though some weeks are louder than others. It’s mostly funny to know so much about the life of the drug dealer who lives above me because he doesn’t bother to consider the sheer extent to which his voice travels down below him.

It’s not the same as being greeted each morning by a chorus of songbirds, no. But sparrows, mourning doves, and my good friends, the city pigeons, do converge in the trees out front to coo and chirp at one another while feasting upon the bits of white rice left out for them by the maintenance men. I also receive a new type of morning welcome: every day during the week, Brian will bid me goodbye between the hours of 6:00 and 8:00 AM, a half-dozing reverie in which I’m gently lifted into his arms and freckled with kisses before plunging unconscious again. And sometimes, as I remove my earplugs and turn my white noise machine off a few hours later, I will catch the shrill music of José whining that “Those fuckers owe me my money.”

My life has continued apace as it had been, more or less, except now I’m just a person whose apartment burned down that one time. This can be fun to bring up if I’m in a humor to make people uncomfortable for a few moments. The other night out at drinks with Brian and some friends, while Brian was caught in conversation elsewhere, a guy attempted to start hitting on me by complimenting the assortment of Jibbitz on my purple Crocs. He inquired if I had more of them back at home and if I changed them out regularly. I hesitated for half a second, before politely replying “Yes, I have two bags of random Jibbitz that I bought on Amazon, and I change them every so often, depending on how I feel.” This was true, at one point—the Jibbitz on those Crocs are the only ones I have left. Sometimes it is funny to just come out with it and say “I don’t actually have that anymore, my apartment burned down,” because then I laugh and assure the other person “It’s ok, I’m ok,” while they look at me with a mixture of concern and horror. But at that bar on a Saturday night, I just wasn’t in the mood to bring the vibe down.

Not long after this interaction, Brian closed out our tab and we called a car. On the ride home, he doubled over asleep in the backseat even though we were only twenty minutes away. It was a short trip compared to most other places we tend to come back from on late nights now, since our apartment is never usually close to them. When we got in, it was after 1:00 AM. I double-checked the burners on the stove, an old habit. It’s grimly ironic now: I’ve always feared that I’d leave them on by mistake and burn down my apartment, and my apartment burned down anyway, without my involvement. Yet I still hold onto that same fear—at this point, I figure it doesn’t hurt to be careful. Right? As I washed up and got undressed, I sensed that Brian was already long gone from this waking world, in my bed that’s not my bed, in my room that’s not my room, but it was home to him anyway. It had to be.

I turned out the lights and curled up next to him. I knew it might not be quiet by the time I woke up, but it was quiet now.